Retracing the actors involved in the various rebrands made visible the specialisation of the trade, with graphic design and advertisement evolving as diverging paths. Furthermore, the lack of discussion led Früh to the conclusion that although from an outside perspective Swissness is perceived as a brand, there is not a similar awareness from inside Switzerland.

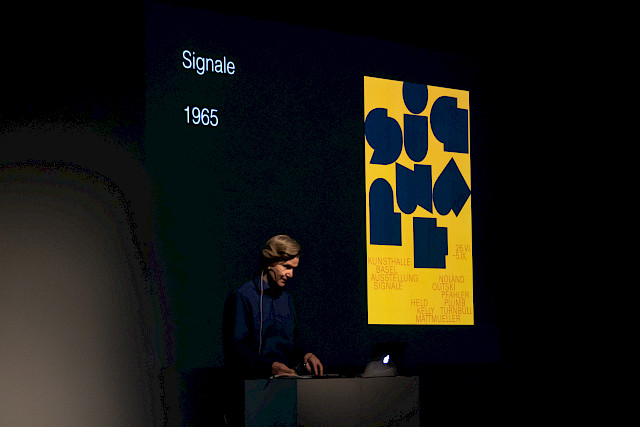

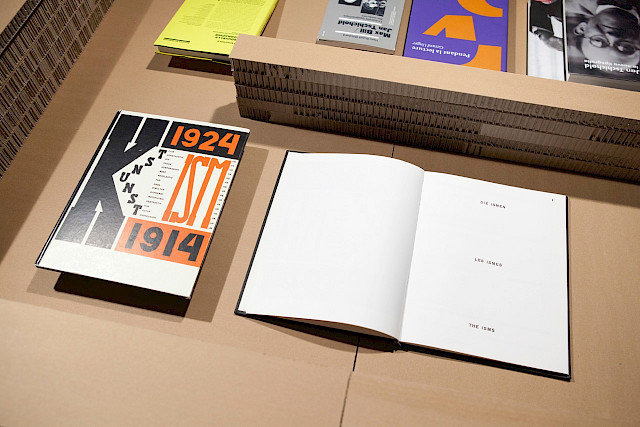

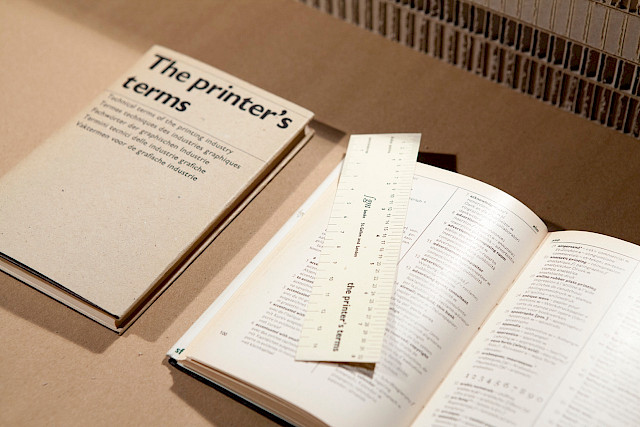

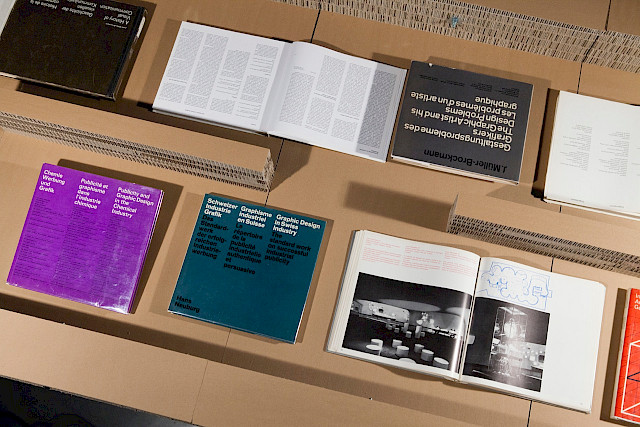

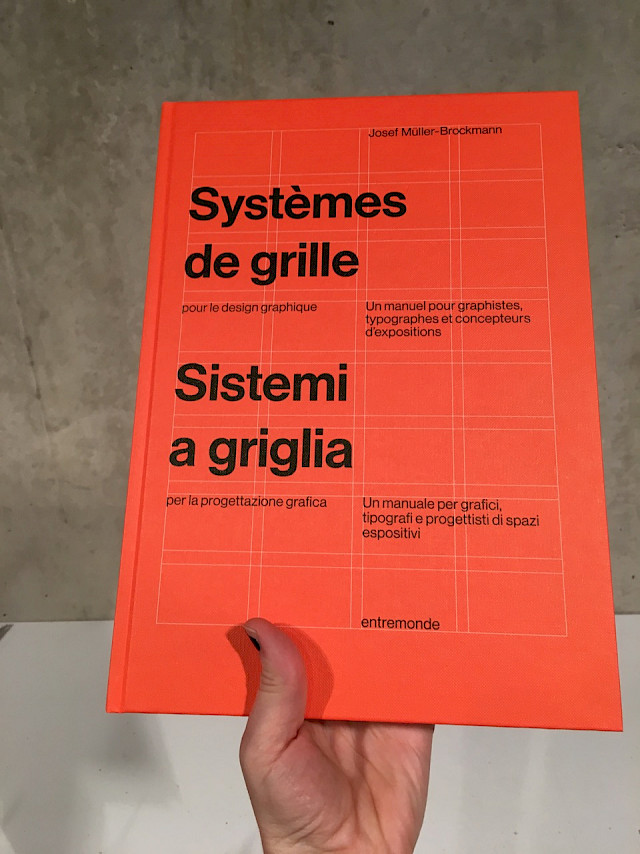

“It all started with Lascaux.” With this strong statement stemming from the opening sequence of Joseph Müller-Brockmann’s History of Visual Communication (1971), Ueli Kaufmann critically analysed modern graphic design narratives which construct the past as progressive development. Self-authored history of graphic design in Switzerland, Karl Gerstner and Markus Kutter’s Neue Graphik (1959), took a positivist approach attempting to show a progression in Swiss design. Despite the claim of continuity made by these books, there are several breaks in the narratives. Furthermore, they tend to evolve from a history of communication to a history of style. Relying on Eric Hobsbawm’s theories dealing with the invention of traditions, Kaufmann questioned the narrative created by the books which ultimately lead to a form of elitism and promote the author’s authority.

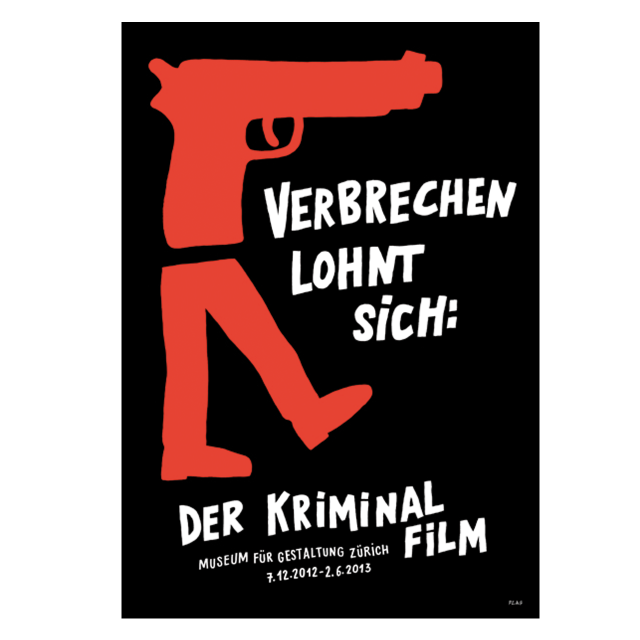

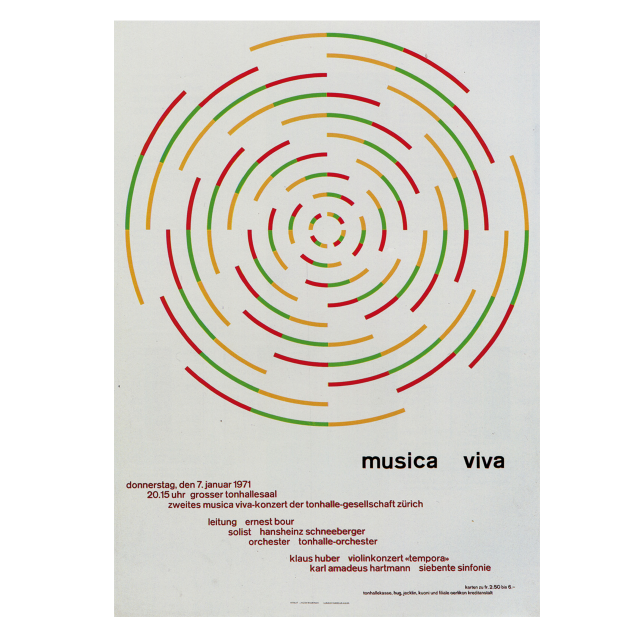

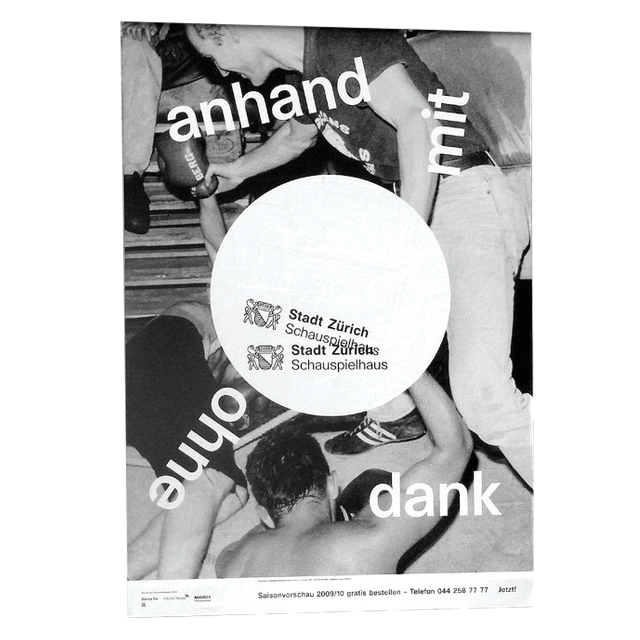

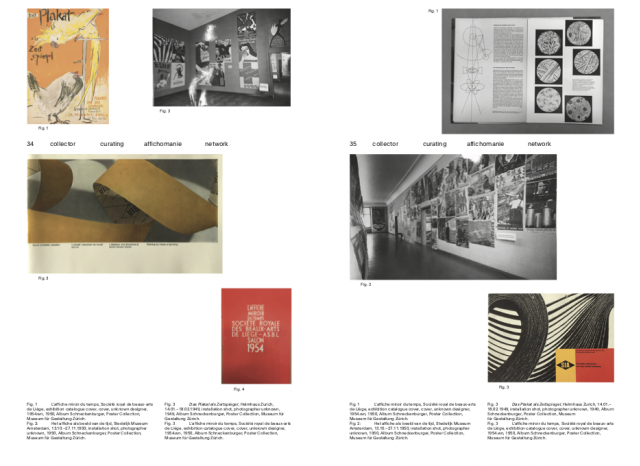

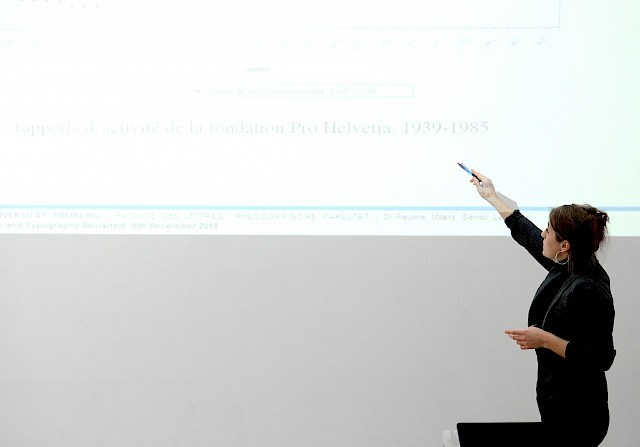

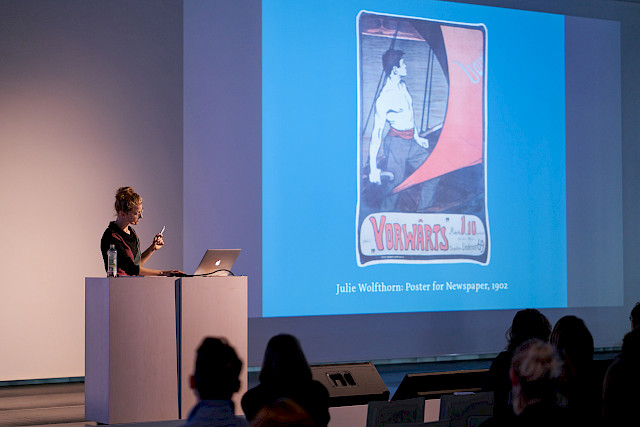

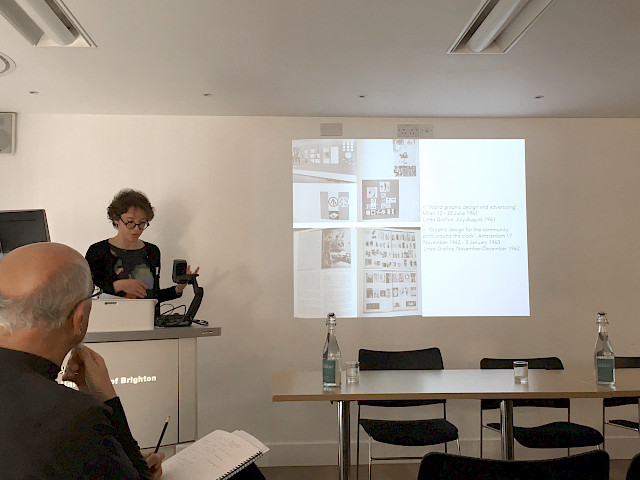

In her presentation, Sara Zeller retraced the history of “The Best Posters of the Year”. The award was started on the initiative of Pierre Bosshard, who attempted to fight back a perceived decline in the quality of posters during the war. Organised by the Federal Department of Home Affairs between 1943 and the late 1990s, the award was initially envisaged as a means to promote the visibility of ‘good’ posters and thus encourage design. In the first years, the poster competition was therefore clearly aimed at the professional community.

However, by the end of the 1940s, the posters increasingly took part in travelling exhibitions that promoted Switzerland abroad. In line with this goal, the travelling posters were not chosen with regards to the quality of their design. Instead, the organisers of the international exhibitions requested posters displaying the best essence of Switzerland such as idealised touristic promotion. The poster award should therefore not only be understood as a means of design promotion but instead be replaced in the wider context of spiritual national defence that contributed to the creation of the image of Switzerland abroad.

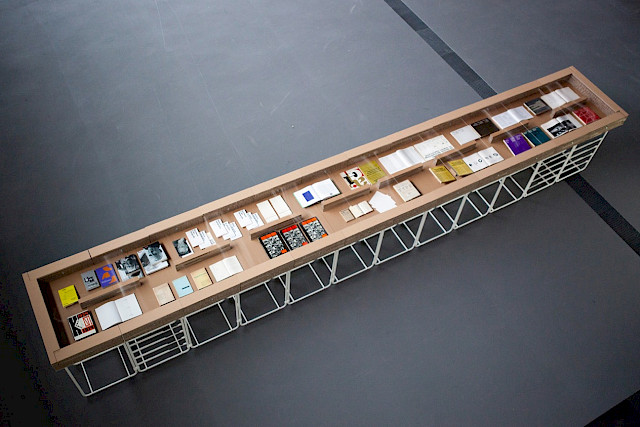

Concluding the morning presentations, associate researcher Julia Meer presented her ongoing publication project centred on the work of Jacqueline Casey and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Office of Publications between the 1950s and the 1980s. The works selected can be connected to broader issues, including gender and the history of technology. Furthermore, the MIT’s publications are a trace of the migration of skills and aesthetics. Julia Meer explained how she aims to connect design and discourse by inviting specialists to contribute to the publication with essays. Furthermore, she highlighted the challenges she is facing as she is confronted with a linear narrative formed around one person and a biased selection of works. Meer thus stressed both her desire to challenge circumscribed perspectives, and her determination to avoid a publication that feels ill-defined due to the many avenues taken by the research.

The morning concluded with a panel discussion which saw the speakers joined by SGDTR experts Jeremy Aynsley and Claude Hauser. As the moderator, Davide Fornari highlighted the role of narrative construction in all the projects, while Claude Hauser highlighted the importance of context and contextualisation. Jeremy Aynsley brought an international perspective by questioning the specificity of Swiss graphic design. He also discussed the discontinuity of modernity, and the role played by conservative modernity, whereby modern means are used to construct a traditional view. Davide Fornari summed up the surprising insights from the morning: exhibition are not necessarily representative of the profession; magazines are not as critical as one would expect; and finally, books are a tool for diplomacy.

Principles of Education

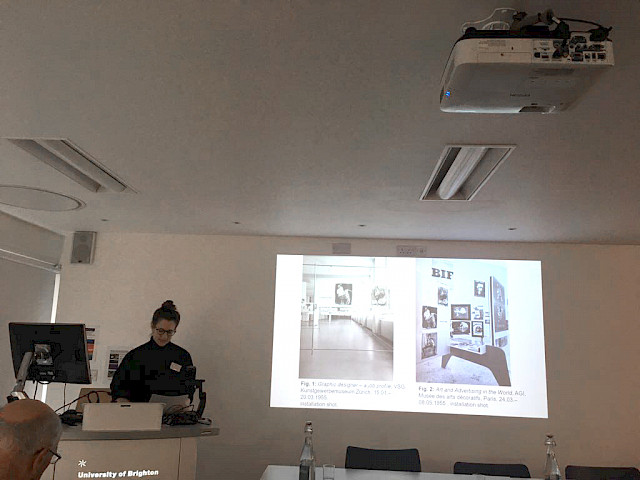

Sub-project A, devoted to principles of design education at arts and crafts schools in Switzerland in the first half of the 20th century, took centre stage in the afternoon during the second day of the SGDTR Experts’ Panel Meeting. In his presentation, Jonas Niedermann discussed the impact on the curriculum of the graphic design course at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Zurich of a Swiss federal law regulating the training in all commercial professions acted in 1939. Based on documents found in the archives of the school, the city, the canton of Zurich, and the professional associations Swiss Werkbund and Verband Schweizer Grafiker, he highlighted the debate these regulations triggered. Whereas the teachers and the professional associations argued that creative processes could not be regulated, the Federal Office for Industry, Trade and Employment encouraged the enforcement of the training regulations in the field of applied arts. In conclusion to his analysis, Jonas showed that Swiss federal law regulating the training in all commercial professions had no significant impact in the Kunstgewerbeschule in Zurich as the Fachklasse Grafik’s curriculum remained unchanged.

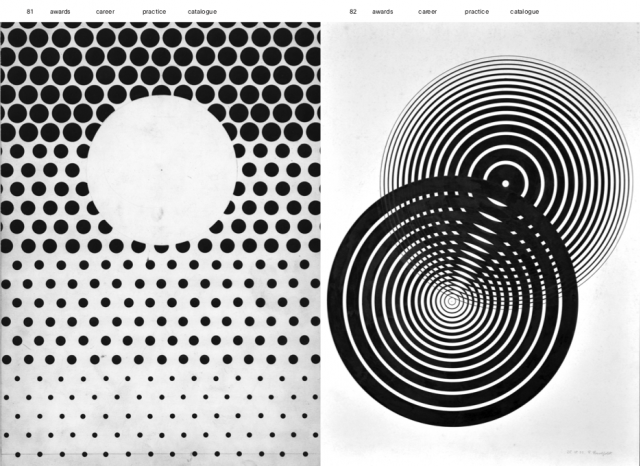

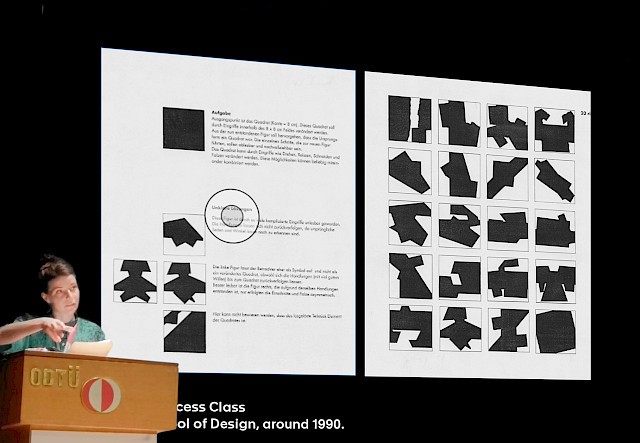

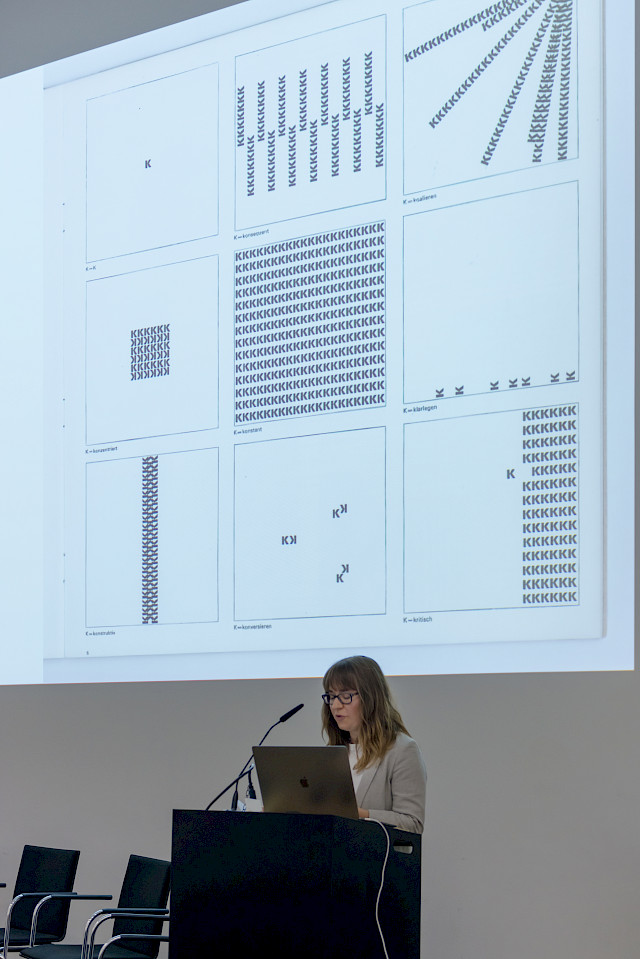

Sandra Bischler approached graphic design education from the students’ perspective through the lenses of the students-led magazine K. Produced and published by the students of the Basel Trade School (Allgemeine Gewerbeschule Basel) between 1963 and 1964, the magazine provides a valuable source to identify and explore graphic design principles. Through a close examination of the visual and textual content of three issues, Sandra revealed how the magazines K focused on the formal quality of the document itself instead of the design process and presented a certain aspect of education which slightly contrasted with the curriculum of the school. Thus, she eloquently argued that these magazines can be located as a site from which to explore the relationships between the students and teachers, and used as devices to unlock potential counter narratives.

The third presentation by Peter Vetter focused on the teaching career of Ernst Keller as presented in the first biography No Style. Ernst Keller (1891–1968) – Teacher and Pioneer of the Swiss Style (Triest 2017), which he co-edited. Keller has been referred to as the “father of Swiss Style”, because under his students were a large number of future celebrities of Swiss graphic design. Nevertheless, his actual contribution to design education and training is rarely approached. Departing from this premise, Peter Vetter illustrated the research journey through archives, primary literature and oral history. As conclusion, he questioned his impact on the Swiss Style since he has neither in his teaching nor in his practice fixed himself on a style, but has designed solutions from the content.